| Oct. 18, 2002: People worry a lot about asteroids. Although the

odds of Earth being hit by a big one are slim, the consequences are

terrifying: tsunamis, climate change, even mass extinction. Fortunately, it

doesn't happen often. Four billion years ago it happened all the time. Our

planet was still young and the inner solar system was littered with

asteroid-sized "planetesimals," the leftover building blocks of planets.

Planetesimals, some big and some small, hit Earth every single day. This

so-called "Period of Heavy Bombardment" (or PHB) lasted from about 4.5 to

3.8 billion years ago--a span that couldn't have been pleasant for

terrestrial life.

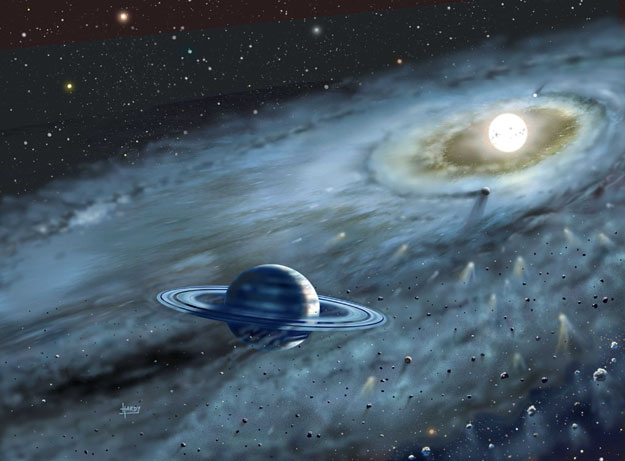

Above:

Planetesimals littered the solar system when Earth was still a young planet.

Earth's early pounding was one of the topics discussed this month when

experts and students from around the world met at "Perspectives in

Astrobiology," a NATO Advanced Studies Institute in Chania, Crete, sponsored

jointly by NATO and the Marshall Space Flight Center. Science@NASA's Ron

Koczor was there, and this is his report:

Participants at the meeting noted something odd about the end of the

Period of Heavy Bombardment. From the earliest geologic records known

(roughly 3.8 billion years old), there is fossil evidence indicating life on

Earth. The existence of apparently successful microbial life so soon after

the end of these cataclysmic bombardments suggests that life emerged on

Earth during the violent PHB itself.

How could that happen? Did comets or asteroids deliver life intact to

Earth? Maybe life rapidly evolved from organic building blocks deposited by

comets. No one knows. Astrobiologists would love to study rocks and chemical

fossils from that epoch, yet because of Earth's wind, rain, earthquakes and

plate tectonics (normal environmental processes), the record has been

completely erased.

Or has it?

Scientists at the conference speculated that such a record does

exist. Not on Earth, but on the Moon.

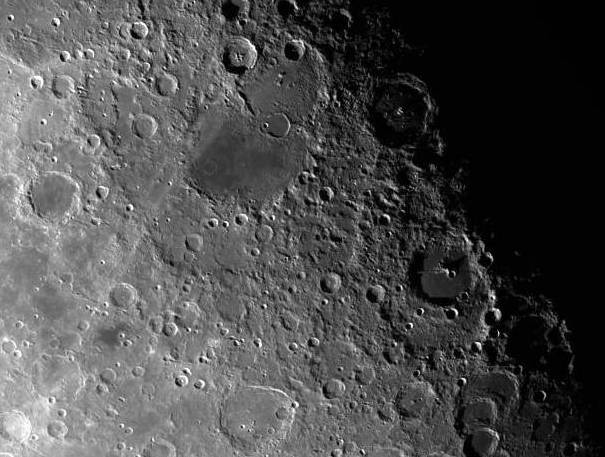

Left:

The Moon is scarred with ancient meteorite impacts that, on Earth, would

have long ago weathered away.

When a large body strikes Earth, impact debris can be accelerated to

orbital speed and achieve Earth orbit. Four billion years ago Earth was

probably surrounded by debris ejected in this way. (The Moon itself is a big

piece of Earth that sundered when a Mars-sized planetestimal hit 4.5 billion

years ago.) During the Period of Heavy Bombardment, the Moon was

considerably closer to the Earth than it is now, perhaps 3 times closer.

This placed the Moon in an ideal position to sweep up some of the

terrestrial debris.

Because the Moon lacks weather or tectonic activity, that debris might

still be there. While some has undoubtedly been destroyed by subsequent

impacts of asteroids or comets on the Moon, some might have survived in the

lunar soil. A recent study by Univ. of Washington graduate students John

Armstrong and Llyd Wells, in collaboration with Guillermo Gonzalez at Iowa

State, suggests that as much as 20,000 kg of Earth material could cover

every 100 square kilometers of the moon.

David McKay, an astrobiologist at NASA's Johnson Space Center, notes that

"the Moon was in a unique position to be a collector of ejecta from Earth.

If we look in the right places, we could find a reservoir of materials for

study."

Right:

Apollo 16 astronaut Charles Duke collects rock samples near Plumb crater on

the Moon.

The

400 kg or so of lunar rocks and soils already on the Earth thanks to Apollo

begs the question: Have such terrestrial materials been seen in any of the

returned samples? According to McKay: no. "I know of no reports of such

materials, but I think the reason may be that no one has actually looked for

them! This is an emerging area of research that was not considered over the

past 30 years since Apollo." The

400 kg or so of lunar rocks and soils already on the Earth thanks to Apollo

begs the question: Have such terrestrial materials been seen in any of the

returned samples? According to McKay: no. "I know of no reports of such

materials, but I think the reason may be that no one has actually looked for

them! This is an emerging area of research that was not considered over the

past 30 years since Apollo."

Where should future astronauts look on the Moon for

these ejected terrestrial materials? There are several possibilities.

One place, according to John Armstrong,

would be the Moon's eastern (as seen from Earth) limb. "The Moon's rotation

about its axis is synchronized with its revolution around the Earth,"

explains Armstrong. This means that the same side of the Moon--its eastern

limb--is always the leading edge as it circles Earth. That leading edge

would tend to sweep up more orbiting debris than other areas.

"This is true for materials that are ejected into high Earth orbit.

Another possibility is that material is ejected and travels directly from

Earth to the Moon. In that case, it would be found anywhere on the

Earth-facing side," said Armstrong. A third possibility is that the Earth

material is ejected into a longer-lasting solar orbit. In this case the

material could have spent thousands or millions of years in orbit and then

impacted the Moon in a more random pattern.

Below:

Moon rocks ejected by asteroid impacts have landed on Earth (the reverse of

the process described in this article). This one was found in Antarctica.

How

could we distinguish an ancient Earth rock from a genuine Moon rock? After

all, the Moon itself is a very old piece of Earth. How

could we distinguish an ancient Earth rock from a genuine Moon rock? After

all, the Moon itself is a very old piece of Earth.

According to Armstrong, that question is still under discussion. "There

are several possible chemical differences," he says. One would be water.

Earth's oceans formed after the Moon split off from our planet. While Moon

rocks are dry, some Earth rocks contain hydrated minerals--those which have

water incorporated into their molecular structure. Other differences could

be the presence of hydrocarbons or carbonates.

Perhaps a series of lunar missions would find such rocks: "We could

develop automated robotic techniques that scan thousands or millions of

small rocks, searching for Earth materials in lunar soils," speculates

McKay. "It would be like looking for a needle in a haystack--a task that

would be nearly impossible if done by hand but easily done by robots. We

simply need to know which properties are the most useful for distinguishing

Earth materials from Moon materials and set the robotic instruments to sniff

them out."

It is often said that traveling makes you appreciate home that much more.

In this case, traveling to the Moon may be the only way we can ever

understand the early chaotic period of Earth's formation.

|